I recently came across some relatively inexpensive 12.8 V, 10 Ah LiFePO4 batteries for sale online under the “Wallaby” brand:

This brand is new to me and doesn’t seem particularly well known online, which leads me to believe that either LiFePO4 batteries are a new entry for this brand, or the brand itself generic and is no different to the other essentially no-name battery brands floating around online. These “brands” typically use old recycled or second-life cells, which is not always necessarily a bad thing so long as you temper your expectations in line with the asking price and rated capacity.

Typically, the recycled cells that those kinds of brands use are from old batteries which have degraded to the point that they can only store approximately 80% of their rated capacity and have since been decommissioned. For example, cells from a battery originally rated at 120 Ah may have degraded to a maximum capacity of 100 Ah over their service life. When these batteries are decommissioned, those same cells are then reused by these no-name brands and resold as a new 100 Ah battery. This way they can get away with using cheaper second-life cells while still technically advertising the rated capacity correctly. Of course, these batteries won’t last as long as newly manufactured ones as they’re well into their life, but with that said they can usually be bought for significantly lower prices than new, equivalent capacity batteries. As usual, it seems that Caveat Emptor applies once again, and it’s up to the buyer to determine whether a shorter lifespan is worth the reduced price.

In my case, given their price and fact that I don’t intend to discharge them particularly deeply in everyday use, I bought two Wallaby batteries and put them to the test.

Upon arrival they were well packaged with each battery individually boxed. They also came with small plastic covers for the terminals which is another sign that the batteries were packed with some care. Physically, the external casing appeared to be brand new and in excellent condition. While, electrically, their voltages were essentially identical, suggesting that they were at similar states of charge – another good sign. So, as I intended to run these batteries in a “24 V” camping system (which for LiFePO4 is more like 27 V), I fully charged them in series using a Victron 75/10 solar MPPT controller, giving the cells enough time to balance, and ran a discharge test through a DL24P electronic load:

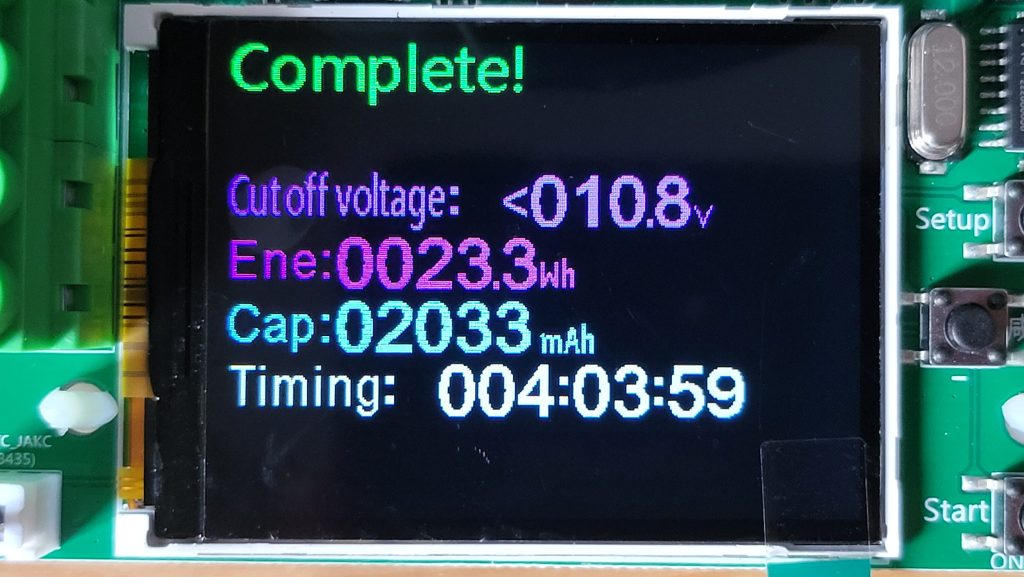

Although I only drained the batteries to 24 V (12 V per battery / 3 V per cell), which should be somewhere in the general region of 20-30% remaining capacity for this battery chemistry, I was able to get over 10 Ah and 277 Wh out of them. Considering that these batteries are rated at 10 Ah and 128 Wh each and that they were relatively cheap compared to others on the market, I have to say that I’d recommend them. Even without opening them to check the age of the cells and whether they’re reused 12 Ah or new 10 Ah cells, it would still be worth it either way in terms of price per watt hour. Of course the big unknown at this point is how long they’ll last, however they haven’t shown any sign of slowing down even with repeated deep discharge tests, so the outlook for the moment looks promising.